Woody Allen told journalists Friday at a press conference for his new rom-com “Magic in the Moonlight,” set in the 1920’s in the gorgeous South of France, that in life what you see is what you get. He doesn’t believe in a spiritual after life. At a press conference in a midtown Manhattan hotel Friday afternoon, the “Annie Hall” director spoke of the meaningless of life and how movies served as a distraction from its misery in a riff as hysterically funny as a stand-up comedy routine.

[springboard type=”video” id=”963719″ player=”tmbg001″ width=”599″ height=”336″ ]

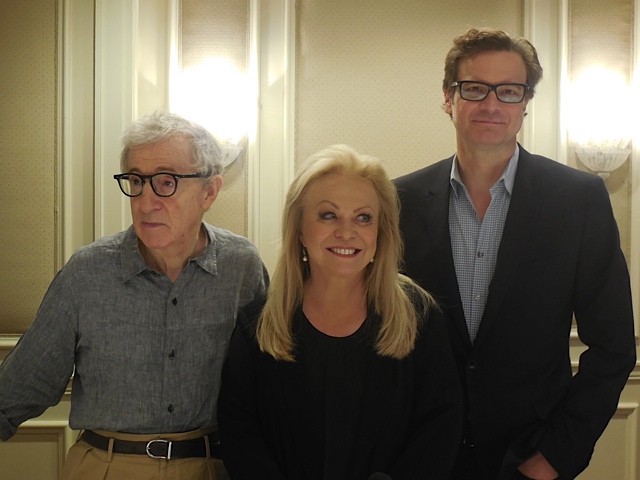

Allen, joined by Colin Firth and Jacki Weaver, fielded questions from the press, who were asked to keep questions pertinent to the film. The “Annie Hall” director was in fine form, witty, talkative and charming. “Magic in the Moonlight” is a frothy comedy about a master magician (Firth) who tries to expose a psychic medium, Sophie Baker (Emma Stone), but then falls for the three decade-younger beauty and begins to believe her psychic powers could be real. Weaver plays a gullible American socialite who turns to Sophie to spiritually reunite her with her beloved dead husband.

Here are edited highlights from the press conference:

Allen on movies as escapism:

I’ve been escaping my whole life. Since I was a little child I escaped into the movies on the other side as an audience member. I escaped by going into the movies and sitting in the movies all day long. And then when I got older I escaped into the world of unreality by making movies, so I’ve spent the last – I don’t know – almost fifty years, not quite, but 45 years, something like that, escaping into movies but on the other side.

When I get up in the morning I go and I work with beautiful women and charming men, and funny comedians and dramatic artists and I’m presented with costumes and great music to choose from and sense and I travel a certain amount of places so my whole year for my whole life I’ve been living in a bubble and I like it. I’m like Blanche duBois that way. I prefer the magic to reality and have since I was five years old. Hopefully I can continue to make films and constantly escape into them.”

On why his protagonists tend to be neurotic and find life meaningless:

“Why do I find life meaningless?… Because I firmly believe – and I don’t say this as a criticism – that life is meaningless. I’m not alone in thinking this. There have been many great minds far, far superior to mine that have come to that conclusion, both early in life and after years of living and unless somebody can come up with some proof or some example where it’s not, I think it is. I think it’s a lot of sound and fury signifying nothing and that’s just the way I feel about it.

I’m not saying one should opt to kill oneself, but the truth of the matter is, when you think of it, let’s say, every hundred years, or certainly every 110 years, there’s a big flush and everybody in the world is gone. Everybody’s gone and there’s a new group of people. And then that gets flushed and there’s a new group of people. And this goes on and on interminably toward no particular – I don’t want to upset you – toward no end, no particular end, and no rhyme nor reason.

And the universe as you know, from the best physicists, is coming apart and eventually there will be nothing, absolutely nothing. All the great works of Shakespeare and Beethoven and Da Vinci, all of that will be gone… So all this achievement, all these Shakespearian plays and symphonies, all of this which is the height of human achievement, all that will be gone completely. There will be nothing, absolutely nothing! No time, no space. Nothing at all. Just zero.

So what does it really mean to get exercised over trivial problems? That’s why over the years I’ve never written or made movies about political themes cause while they do have current critical importance, in the large, large scheme of things, you know, only the big questions matter and the answers to those big questions are very, very depressing. What I would recommend? This is the solution I’ve come up with, is distraction. That’s all you can do. You get up. You can be distracted by your love life, by the baseball game, movies, by the nonsense, can I get my kid into this private school? Can I get this girl to go out with me Saturday night? Can I think of an ending for the third act of my play? Am I going to get the promotion in my office? You know, all this stuff, but in the end the universe burns out. So I think it’s completely meaningless and to be honest my characters portray this feeling.

Have a good weekend!”

Woody Allen on the filmmaker’s purpose:

I think it’s the artist’s job, I think it’s my job or the artist’s job, to try and find some solution or some reason to accept things but given the grimmest reality, I feel the grimmest facts are the real facts, the true facts, that you’re born, you die, you suffer, it’s to no purpose and you’re gone forever, ever, ever, and that’s it. And facing that that massive, massive overwhelming bleak reality to find a reason to cope with that, a good way to cope with that, and I feel it’s the artist’s job to do that. I’ve never found a good solution to it and the best that I can offer is distraction.

The artist can’t give you an answer that’s satisfying to the dreadful reality of your existence so the best you can do is maybe entertain people and refresh them for an hour and a half and then they can go on and meet the onslaught until they are sunken and crushed and then somebody else comes along and picks them up a little bit.

Aren’t you glad you came today?

Allen on reality and illusion as a theme of the film and how it melds with the film’s setting in the 1920’s:

I’m all for illusion cause as you can tell from what I’ve been saying, for me reality is a painful grind and I think it is for everybody regardless of whether one is rich or poor, in the end. I’m going to quote myself, there was a line in a movie, I can’t remember which movie it was, but it was, ‘We all know the same truth, our lives depend on how we choose to distort it.’ And that’s how I feel so I’m all for illusion.

I’ve done this before in films, in “Purple Rose of Cairo,” the film is all about the difference between reality and illusion and how much better illusion is. But the problem is in that movie Mia Farrow had to chose between reality and illusion and she had to choose reality cause if you choose illusion it’s crazy. You can’t. You just go mad, so she chose reality and it hurt her in the end.

The same thing is in this movie. The reality is in marked contrast to the illusion. Colin works as an illusionist. That’s what they’re called. The type of magician he is. He’s not a sleight of hand artist or a telepathic. He’s an illusionist. He creates these illusions and I feel that’s the only the only thing that gets you up. The only thing that could possibly save us from the plight that we’re all in is some kind of act of magic and unless it happens soon, you know, it’s a grim situation so I am obsessed with that subject.

The 1920’s for us now – I’m sure if you lived at the time it wasn’t that way – but what happens is your mind helps create an illusion when you cast something in the past, when you state something in the past, and the 1920’s for me is all flappers and beautiful cars and jazz music and bootleggers and a different way of life. I’m sure if you lived there at the time it was not so great, but now, with the years intervening one can soften it and make it into anything you want and I do that all the time and set films very often in the past because I can create the illusion more tantalizingly.

Allen on whether he was concerned Colin Firth’s character would alienate audiences because he was so sarcastic and possibly unlikeable:

Throughout history in the theater and film people do like sarcastic characters and they do like curmudgeons if they’re amusing. They do like them despite the fact that they’re vitriolic, particularly if they’re for the right thing. If you can see that the person is a decent person and is for the right and is not just a nasty person with base motives but someone who is a decent human but expresses himself, he’s annoyed with the phoniness of the character, the duplicity of the world. A character in the Salinger novel, Holden Caulfield, or “The Man Who Came to Dinner,” the Kaufman and Hart play, people who are vitriolic and find fault with everything, but you love them because they’re decent.

Hypocrisy, phoniness, people who are exploiting the ignorance of other people, human ignorance, so I thought that if the character Colin is playing he wants nothing more than to be wrong. He wants nothing more to find out there is more to life and that he’s wrong and that Emma is right that there’s are things that are unknown to us and magical and amazing and we don’t have all the answers, but the truth is pretty much what you see is what you get. But as soon as he’s deceived into thinking there may be more to life, there may be some purpose or magic or underlying mystical meaning it changes him completely; he smells the flowers. He loves everything. It gives you a purpose in life.