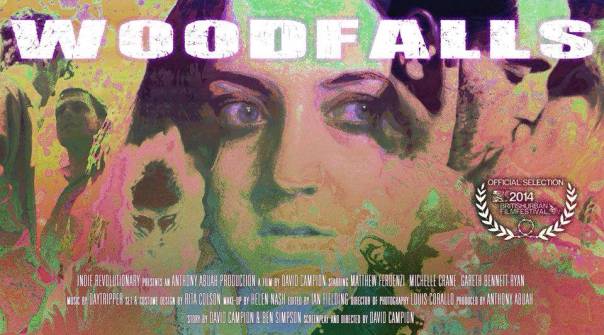

Woodfalls has one thing going for it—Michelle Crane. Crane plays Rebecca, who, along with her brother, Billy (Matthew Ferdenzi), and their helpless mother, moves into a trailer sitting lonely in a field in the town of Woodfalls. Crane, as the bible clinging, inexperienced, softhearted Rebecca is natural and competent in a way no other aspect of this film is. Everything else about Woodfalls—writing, action, cinematography, character, tone, good sense and logic—fails.

Billy, Rebecca and their mom are Irish gypsies, and though my uncle says you can’t trust a gypsy, I think Irish ones are generally less shifty. Irish or not, their presence in Woodfalls particularly upsets a young man, Damon (Gareth Bennett-Ryan), who, between his father’s gruesome confrontation with some drug dealers and an impromptu make out session with his step mom, really needs somewhere to channel his angst. He unleashes his rage onto Billy and his family, and for the opening third of the film their street rivalry is the center of conflict.

Told in three sections, Damon’s plotline opens the film, but as we move onto Billy (and eventually Rebecca), Damon is dropped out of sight, saved and forgotten like the poems of my college days. Damon’s the ultimate device—he’s a major character existing simply to jumpstart the narrative, to give Billy and Rebecca an antagonist.

Billy and Rebecca just want to fit in, but apparently Irish gypsies don’t know how to drink and party (which has to be a steep factual inaccuracy). Billy revels in his newfound freedom and irresponsibility, finding some locals to befriend and get drunk with. He forgets to protect the family trailer, as well his family inside of it, but at least he’s getting some action from a local single-mom—who happens to be Damon’s ex (Woodfalls would adapt perfectly as a soap). Billy likes drinking more than he values family—who doesn’t? His struggle, not only with Damon, but with his compromised moral code (boys just want to have fun) actually makes for a good character study. However, Matt Ferdenzi’s terrible delivery and inexpressive performance makes Billy more like a cardboard cutout with a voice box. He doesn’t give any life to a character desperate for breath.

Rebecca doesn’t navigate the nightlife as well as her brother. In an uncomfortable ten minutes near the film’s climax, she loses her innocence, virginity and sanity in one swoop. But instead of coping with her trauma by turning to the cloth, she grabs a gun and gets some good old revenge. In another film—like Wes Craven’s wonderfully horrible Last House on the Left—this type of rape-revenge would work (for a certain audience). In fact, an entire subgenre of exploitation films center on this very subject matter. Woodfalls is kind of like an exploitation movie, though it’s clawing for deeper dirt, sniffing for a root cause to the violence it depicts. As is, it’s a cross of gypsy-exploitation, superficial character studies, and bad filmmaking.

Writer/director David Campion missed just about every opportunity to put his stamp on this film. There’s no mise en scène, the dialogue is horrid, and the plot management if disproportionate. It didn’t feel like he directed much of anything. The energy is too serious, and yet the seriousness doesn’t lead to profoundness. No two notes flow together in harmony, leaving Woodfalls out of key no matter what tone it strikes. The most enthusiasm Campion musters is for the house music he pumps into the movie, courtesy of a DJ mysteriously introduced as “The Daytripper” in the opening credit sequence. I don’t know how house music fits in with a story of prejudice, trauma, rape and revenge, but maybe it’s a European thing.

I Give “Woodfalls” 3.5 out of 10